Honorific Speech

In Japanese language the way of speaking changes according to the social relations between interlocutors.

I’m not talking about generic forms of respect like putting “Mr” or “Mrs” before the name.

In Japanese we use completely different words and verbal constructions depending on my social status in relation to the social status of the person I am talking to or about.

Japanese honorific forms are one of the most complex and articulated linguistic social systems in the world and one of the greatest difficulties that those who are learning Japanese face.

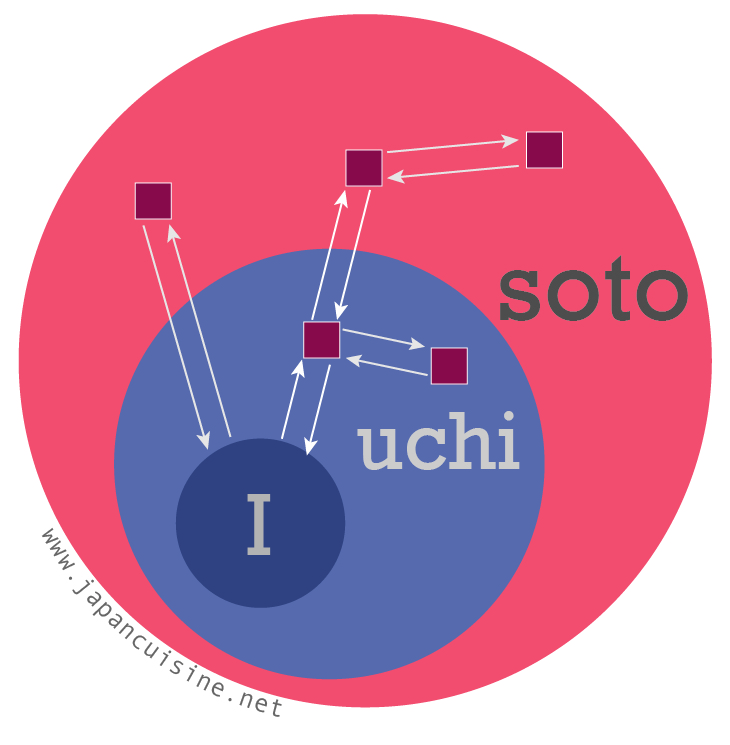

Uchi VS Soto

At the heart of this system of Japanese honorific forms there is the speaker and his world, which includes family and friends. It is the UCHI, which can be translated as “internal”.

All those who do not fit into this “fence” are SOTO, i.e. strangers.

This is the typical scheme used to understand the relationship between uchi and soto when we need to choose verbs and words.

Special People

Within SOTO there is also a sub-group of special people, who are considered to be superior because their age and experience make them worthy of additional respect, or because of the position of prestige and social importance they hold. They are generally those you call “sensei”: teachers, doctors, members of parliament, etc.

Giving and Receiving

Analyzing the variants and the use of the verbs “to give” and ” to have” is the best way to understand how this system works.

Ageru

I’m giving my dad a book. (me→uchi)

My dad gives a book to the neighbor. (uchi→soto)

John gives a book to Mary. (soto→soto)

For all these cases you can use the generic verb: AGERU.

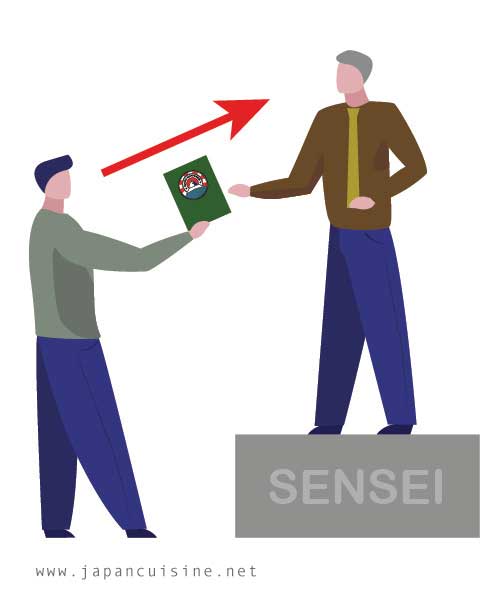

Sashiageru

I give the professor a book.

If my interlocutor belongs to soto and is considered a person worthy of special respect, the verb is SASHIAGERU.

If you want to translate it literally, you could use the word “raise” that shows the elevated position of my interlocutor. Like saying “I raised the book to the professor”.

Yaru

“I give a book to the baby.”

If my interlocutor is clearly inferior to me, the verb used is YARU. I can use it with children, younger brothers and sisters, or a pet. It is also used between close male friends.

If you want to translate it literally, you could use the word “throw”. “I threw the bone to the dog.”

Kureru

John gave me a book

Kureru is the generic form when a soto gives something to an uchi or an uchi gives something to a speaker.

Kudasaru

“The master gave me a book.”

KUDASARU is used when someone superior of the soto sphere gives something to me or my uchi. It could be translated literally as “the master lowered me a book”.

Morau

“I got a book from John.”

When the speaker receives something from someone, the generic verb used is MORAU. It also applies to exchanges soto→soto, uchi→uchi, uchi→soto.

Itadaku

“I got a book from the professor.”

It is the verb used when the speaker, or one of his uchi, receives something from someone in the soto sphere, identified as belonging to a category of great respect (see above).

Combinations

The whole system of verbs illustrated so far applies to other situations where someone does something for someone else. In sentences like:

- My mother makes me sushi.

- The teacher explains the lesson to me.

- I’ll pet the cat.

It joins the specific verb (cooking, explaining, caressing) to the verb give/receive more appropriate for relationships between subjects (kureru, itadaku, yaru, morau, etc.).

If it seems very complicated, it’s because it is.

Other Verbs

It obviously it isn’t over yet. The soto-uchi honorific system and the subgroup of people worthy of particular respect, applies in many other aspects of the Japanese language such as the choice of verb.

Eat

The verb eat best exemplifies how different the words used can be according to the context and the people involved in the action.

The most common verb for “to eat” in Japanese is TABERU.

However, in the sentence “the professor eats“, the verb I use is MESHIAGARU.

If I am among male friends with whom I have confidence and I say “let’s go eating” the verb used will be KUU.

Respect and Modesty

There can be many examples like this. They are different verbs depending on the people the action refers to or different verbal constructions.

Some of these have the task of “elevating” an interlocutor worthy of particular respect, others “lower” the one who speaks in front of an important person.

The underlying constructions and concepts can be particularly complicated. Even the Japanese themselves have difficulty in mastering the subtleties of this system, especially if they do not have to deal on a daily basis with situations that require high levels of formality. Those who have to use this language for work, even if Japanese, normally receive specific training on grammatical forms of respect.

Few Examples

| Verb | Standard Form | Honorific Form | Humble Form |

| To see | Miru (見る) | Go-ran ni naru (ご覧になる) | Haiken suru (拝見する) |

| To say | Iu(言う) | Ossharu (仰る) | Mosu (申す) |

| To do | Suru(する) | Nasaru (なさる) | Itasu (致す) |

| To come | Kuru(来る) | Oide ni naru (御出でになる) | Mairu (参る) |

| To meet | Au(会う) | O-ai ni naru (お会いになる) | O-me ni kakaru (御目に掛かる) |

As you can see they are not different conjugations or ways to use the same verb. They are completely different words.

The last example that I want to share to definitively scare you in case you are thinking of starting to study Japanese is on the first person singular pronoun.

I

Even a word as simple and immediate as “I” in Japanese changes depending on the person I’m talking to. In a nutshell, there are many different versions for saying “I”. And to avoid being rude, they should be used with extreme caution and accuracy.

Watashi – 私

The most generic word used to indicate “I” in Japanese is “watashi”. Actually there are some variations of this first version too.

- In a very formal speech, when speaking in public, it can become “watakushi”, or “ware-ware” to say “we” if I speak on behalf of a group of people.

- A woman, in an informal situation, with friends, relatives, with her partner, can use the abbreviation “atashi”.

- An authoritative person, perhaps of a certain age, in front of younger interlocutors or talking to someone in a much lower position, could use the contracted form “washi” or “ware”. The latter, however, can also be a singular second person!!

Boku – 僕

A man, with friends of the same social level (classmates, teammates peers, etc.) will use the word “boku”.

A woman will never use this word.

Ore – 俺

A man, in an informal situation between people of equal or lesser rank in terms of age, prestige, job position, can use the word “ore”, in which, however, there is a nuance of strong assertiveness. It may be fine between in a group of mates of a sports team, but should be used with great caution because it can be rude. It is an exclusively masculine word.

Uchi – 内

Those who talk about themselves, but as a member of a group of which they are part, family, class, company in which they work, will use the pronoun “uchi”, which is a middle way between me and us.

Watashi, watakushi, atashi, washi, ware, ware-ware, boku, ore, uchi, I don’t think there are other languages in the world that have so many versions and variations to express the simple word “I”.

If you know any, let us know in the comments.